Converting SSE intrinsics code to Neon. Burst masked occlusion culling

The Project

Our amazing Geometry and Lighting team was working on a high-performance implementation of masked CPU occlusion culling based on Intel’s algorithm. The team has done some mathematical and programmatical improvements to the algorithm, and implemented it for Intel using SSE intrinsics and targeting SSE4 CPUs. Felix Klinge and I joined the project at a later stage to add an Arm Neon implementation, too.

Some important background. The project was a part of the Unity Entities Graphics package, so the source code is available - or at least was available at the time of development - as a preview version. The code is written in C# (more specifically, in HPC# - a subset of C# which doesn’t support reference types, and for that reason generates no gargbage) using Unity Burst compiler.

Unity Burst compiler (shortly named Burst) is a tool based on LLVM which translates HPC# into high performance machine code, leveraging vectorization and many other optimization techniques. I am honoured to have worked on Burst for some years together with the outstanding Burst team (Alexandre Mutel, Andreas Fredriksson, Lee Hammerton, Neil Henning, Tim Jones, Marco Persson, Fabrizio Perria), pushing forward Arm-related features - one of them being the Neon intrinsics. Burst supports both Intel (SSE/AVX) and Arm (Neon) intrinsics and allows you to write your wannabe-assembly code in C#.

So, Felix and I had these things at our hands:

- ready implementation of the occlusion culling for Intel

- Neon intrinsics support in Burst

- test projects

- profilers

Basically, we had to translate the SSE code to Neon, and optimize it where possible.

Burst C# Neon intrinsics

During our partnership with Arm, based on the SSE work by Andreas Fredriksson and under his supervision, I designed and implemented C# Neon intrinsics support in Burst. The API surface matches Arm’s C API (ACLE) very closely. The major difference is that vectors were not typed in C#, it’s just a vector of 128 bits, and you as the programmer must use the correct intrinsic function to process it in a correct way. You can potentially call an int operation on a vector of floats - which leads to an incorrect result that is hard to debug - while in C it would’ve been a compiler error. However, it also enables for easier use of data manipulation tricks; you can learn few of them from Andreas’s talks.

On the other hand, for bitwise operations, the vector element type doesn’t matter - AND remains AND, so having a typed version doesn’t really help you much - or doesn’t even make sense.

Fun story; as you may know, naming is one of the major problems in computer science. Neil Henning suggested we use BOB128 (BOB = Bag of Bits) and I found this name super cool.

Because of the typed overrides (which sometimes do the same thing - for example, for bitwise operations) the number of Neon intrinsics is huge, so I did a categorized summary table which makes searching easier.

For more information on the intrinsics and their usage, you could refer to talks recorded by our friends at Arm and myself:

Using Burst Compiler to optimize for Android - Unite Now 2020

Arm @ GDC 2021 : Supercharging mobile performance with Arm Neon and Unity Burst Compiler

Translating to Neon

So, we had the SSE code written in HPC# using Burst intrinsics, and started “converting” it to Neon.

To easier match SSE intrinsics to Neon, one can use the amazing SSE2Neon lib, with source code available here. Of course, it’s all written in C, but it’s invaluable in our task because translating the code to C# is super easy - as I mentioned before, the API matches Arm’s C API (ACLE) very closely.

Unsurprisingly, it appears that most of the common math operations have equivalents for both Intel and Arm. Of course, the parameter order is often different - just so that your life would not be that easy :) One of the examples is multiply-subtract:

fmsub_ps(a, b, c) => a * b - c

vmlsq_f32(a, b, c) => a - b * c

Some of the “problematic” Intel instructions are shuffle and movemask. They appear to have no equivalent in Neon.

Overall, shuffle as a “random” element manipulation routine is available in Intel but completely missing in Arm. This may seem as an advantage for Intel, but in fact, when solving problems, you rarely need a truly random manipulation. You have to be creative and know the instruction set to come up with a solution to the actual problem. Okay, if you’re out of ideas, bitwise select BSL or its ACLE equivalent vbslq_s8() can do the job too.

movemask represents a group of instuctions that manipulate a scalar next to vector variables. Packing a mask into an int is not an uncommon pattern in SSE world; it might be a legacy thing caused by some microarchitectural decisions, I am not aware of the true reasons behind this decision. In the Arm world, as far as I know, ADDV and friends is one of the several ways to get a scalar out of a vector; in other cases, you have to be creative… or solve the actual problem in a different way. In our case, the target SSE level wouldn’t allow for a shift by register, so the team had to calculate and use intermediate scalars. On the other hand, Neon supports shift by register by default (ACLE method vshlq_s32()), so we were able to get rid of some tricky instructions in the most efficient way.

To be honest, I didn’t find a good strategy to check if the Intel and Arm code written in CPU intrinsics is “equivalent”. You can try doing some debugging with data… but a) it’s really hard when you have much data b) unfortunately you cannot debug Neon intrinsics in Burst for a number of reasons. So what I did is leverage the code review skill, do IDE split screen, and compare the Intel and the Arm code line by line. It appeared to work out in the end, we finally had the test working correctly.

Optimizing

Okay, now that we have the feature working from a functional POV, we can start profiling it and see if we can offer some optimizations for the team. Ideally, we wanted to find some optimizations which will benefit both Intel and Arm implementations.

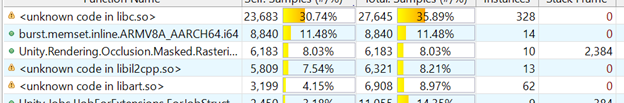

We profiled the test project on an Android phone: Samsung Galaxy S22; it has a single Cortex X2 core (big), three Cortex A710 (medium) and four Cortex A510 (small cores, mostly unused by Unity). As usual, we used the Unity Profiler, then gathered Perfetto (systrace) and a sampling profile (Arm Streamline).

The sampling profiler works quite well even with Bursted code. If you think of it for a moment, it’s C# code that is translated into LLVM IR and then into assembly… but the symbols work (!!) and you get basically a link from the assembly to the line of your C# code (!!) which is super amazing.

There are several stages (jobs) of the culling process, RasterizeJob being the longest and the most important.

So Felix and I looked at the profile and found that third of the time in RasterizeJob is spent allocating. Once again, this is C# and Burst, it’s not a heap allocation because it’s not allowed, but some kind of temp on-stack allocation… which by .NET standard requires zeroing the allocated memory - and takes most of the time.

We removed the allocation of these temp data structures by making it more permanent. Yes it means slightly increased memory usage, but the CPU time spent in RasterizeJob was cut by 2.3x.

The screenshot was taken on Intel; on Arm, the CPU total time went down from ~15ms per frame to ~4ms per frame, or 3.75x faster.

Not bad, and benefits both CPU architectures which is great!

DecodeMaskedDepthJob

Another nice optimization was made to DecodeMaskedDepthJob. It’s a job that is only used when Depth or Test debug views were active - something a developer would use in the Editor, but not something which runs in production. I would say, this is a classical SIMD improvement.

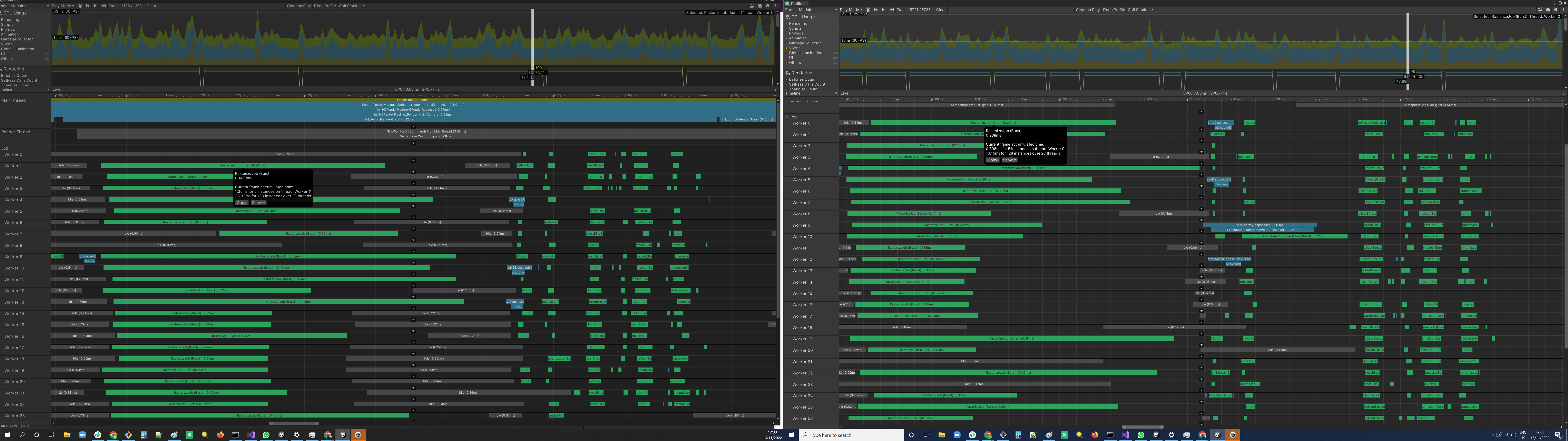

This is a test scene rendered in normal mode. Screenshot taken from an Android device:

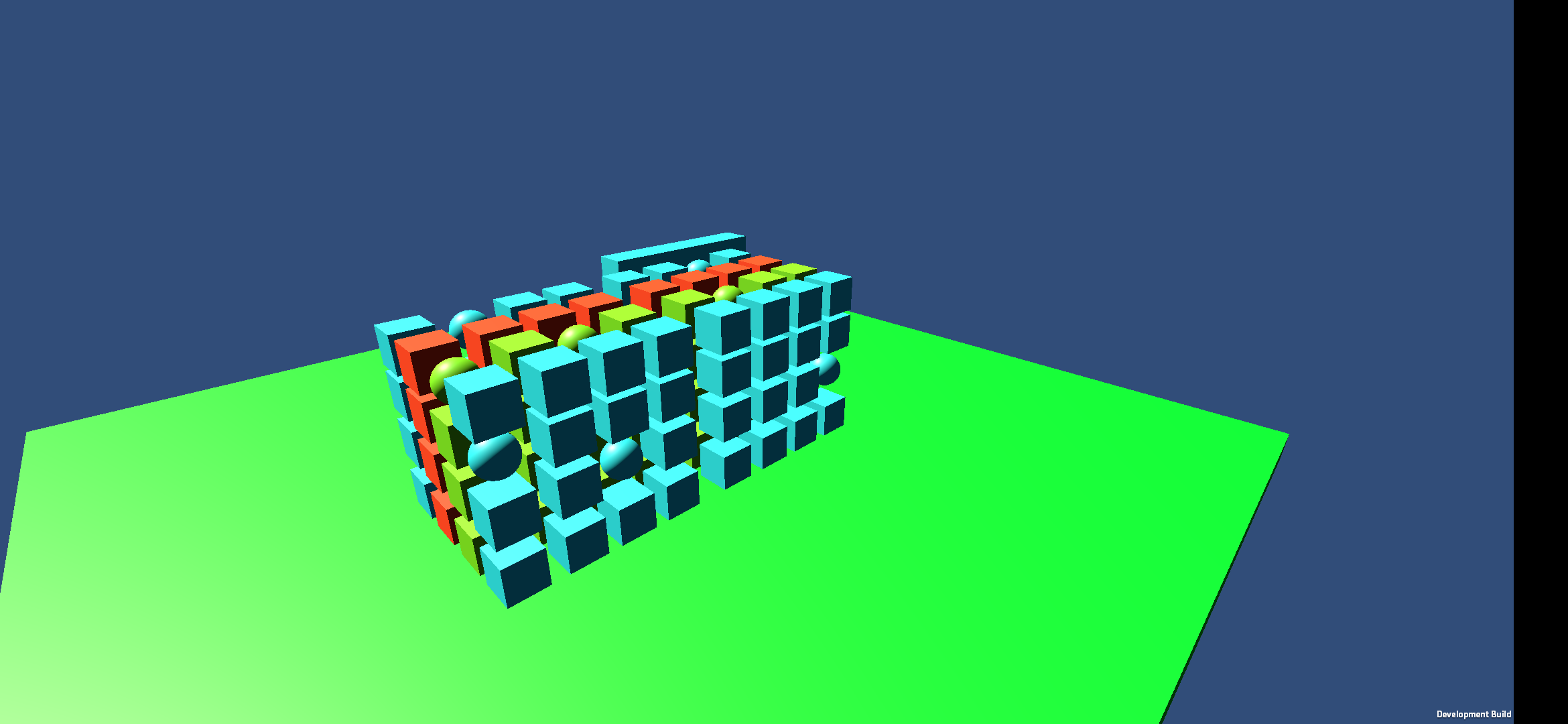

Same scene as above, depth view. Screenshot taken from an Android device:

Same scene as above, test view. Screenshot taken from an Android device. Game objects marked red were culled from the scene:

The original code was processing data at a per-pixel basis; the resulting depth float was selected based on the bit in the mask, something like this:

// i -> input tile index

int x = i % NumPixelsX;

int y = NumPixelsY - i / NumPixelsX;

// Compute 32xN tile index (SIMD value offset)

int tx = x / BufferGroup.TileWidth;

int ty = y / BufferGroup.TileHeight;

int tileIdx = ty * NumTilesX + tx;

// Compute 8x4 subtile index (SIMD lane offset)

int stx = (x % BufferGroup.TileWidth) / BufferGroup.SubTileWidth;

int sty = (y % BufferGroup.TileHeight) / BufferGroup.SubTileHeight;

int subTileIdx = sty * 4 + stx;

// Compute pixel index in subtile (bit index in 32-bit word)

int px = (x % BufferGroup.SubTileWidth);

int py = (y % BufferGroup.SubTileHeight);

int bitIdx = py * 8 + px;

int pixelLayer = (IntrinsicUtils.getIntLane(Tiles[tileIdx].mask, (uint) subTileIdx) >>

bitIdx) & 1;

float pixelDepth = IntrinsicUtils.getFloatLane(

pixelLayer == 0 ? Tiles[tileIdx].zMin0 : Tiles[tileIdx].zMin1,

(uint) subTileIdx

);

// Save back

DecodedZBuffer[i] = pixelDepth;

The new implementation was working on a per-tile basis, and used SIMD to select between layers:

// this is a 32x4 tile

var tile = Tiles[i];

int numTilesX = NumPixelsX / BufferGroup.TileWidth;

int numTilesY = NumPixelsY / BufferGroup.TileHeight;

int tx = i % numTilesX;

int ty = i / numTilesX;

// iterate over the four 8x4 subtiles

for (int j = 0; j < 4; j++)

{

// prepare two vectors of zMin0 and zMin1

// splat j's element

var subTilez0 = new v128(IntrinsicUtils.getFloatLane(tile.zMin0, (uint)j));

var subTilez1 = new v128(IntrinsicUtils.getFloatLane(tile.zMin1, (uint)j));

var testMask = new v128(1, 2, 4, 8);

// the mask is 32 bit, 8x4 bits

// iterate over each byte

for (int k = 0; k < 4; k++)

{

// extract mask for the subtile

byte subTileMask = IntrinsicUtils.getByteLane(tile.mask, (uint)(j * 4 + k));

// now, make low and high half-bytes into a int32x4 mask for blending

// high

int highHalfByte = subTileMask >> 4;

var highMask = new v128(highHalfByte);

// low

int lowHalfByte = subTileMask & 15;

var lowMask = new v128(lowHalfByte);

if (Arm.Neon.IsNeonSupported)

{

var blendMaskHigh = Arm.Neon.vtstq_s32(highMask, testMask);

var zResultHigh = Arm.Neon.vbslq_s8(blendMaskHigh, subTilez1, subTilez0);

var blendMaskLow = Arm.Neon.vtstq_s32(lowMask, testMask);

var zResultLow = Arm.Neon.vbslq_s8(blendMaskLow, subTilez1, subTilez0);

int index = ((NumPixelsY - (BufferGroup.TileHeight * ty + k)) * NumPixelsX + BufferGroup.TileWidth * tx + BufferGroup.SubTileWidth * j);

// save to DecodedZBuffer

// this generates STP which is most efficient

Arm.Neon.vst1q_f32(zBuffer + index, zResultLow);

Arm.Neon.vst1q_f32(zBuffer + index + 4, zResultHigh);

}

else if (X86.Sse4_1.IsSse41Supported)

{

var invBlendMaskHigh = X86.Sse2.cmpeq_epi32(X86.Sse2.and_si128(highMask, testMask), X86.Sse2.setzero_si128());

var zResultHigh = X86.Sse4_1.blendv_ps(subTilez1, subTilez0, invBlendMaskHigh);

var invBlendMaskLow = X86.Sse2.cmpeq_epi32(X86.Sse2.and_si128(lowMask, testMask), X86.Sse2.setzero_si128());

var zResultLow = X86.Sse4_1.blendv_ps(subTilez1, subTilez0, invBlendMaskLow);

int index = ((NumPixelsY - (BufferGroup.TileHeight * ty + k)) * NumPixelsX + BufferGroup.TileWidth * tx + BufferGroup.SubTileWidth * j);

v128* zBufferSimd = (v128*)zBuffer;

zBufferSimd[index / 4] = zResultLow;

zBufferSimd[index / 4 + 1] = zResultHigh;

}

}

}

Please notice that there is a relatively small piece of code that is architecture-specific, and is guarded by IsNeonSupported and IsSse41Supported properties. Don’t worry, the expressions are being evaluated in compile time, and the unneeded branch is eliminated as dead code during optimization.

This is a classical scalar->SIMD transformation. Instead of working with a single float, we switch to processing bigger chunks of data (2x4x4 128-bit vectors), plus we do it using intrinsics and even adding some micro-optimizations (saving two vectors at consequent addresses generates the store pair STP instruction on Arm, which is most efficient).

If you don’t write intrinsics but still switch to processing bigger chunks of data with older scalar code, the compiler may have auto-vectorized the code… or may have not as well. Using intrinsics here paid back with amazing results.

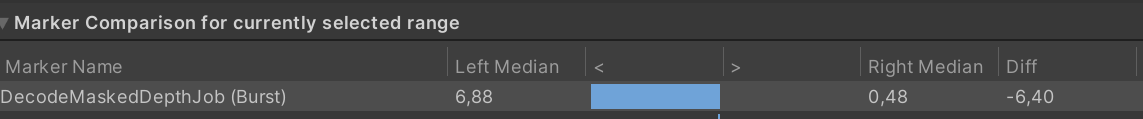

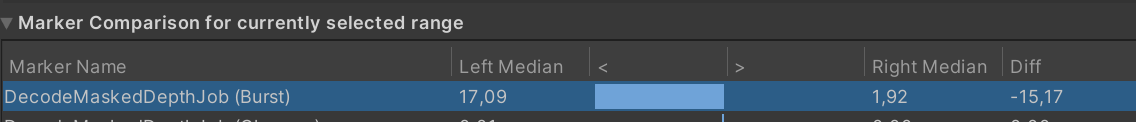

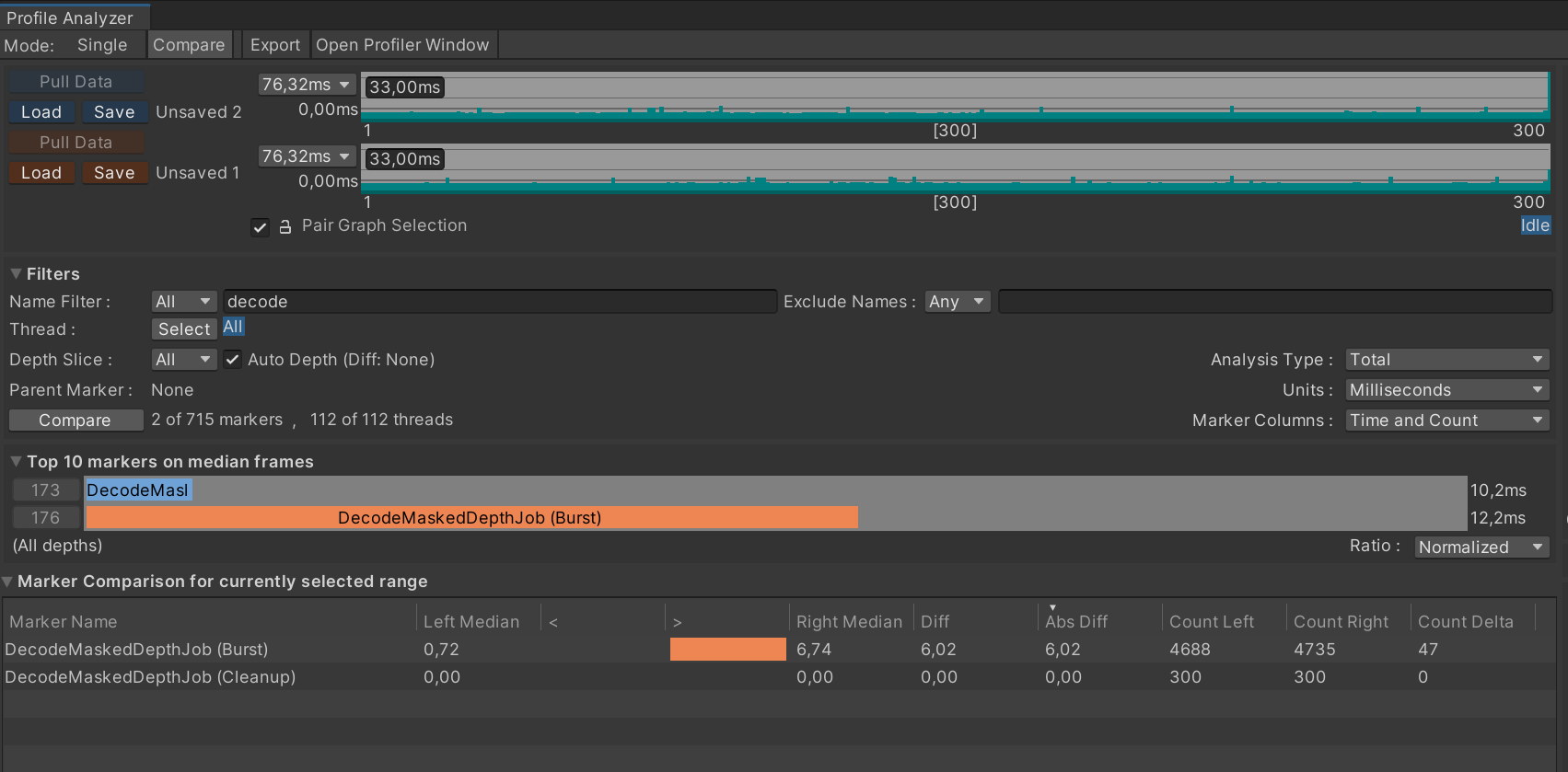

Overall performance gains using new implementation ranged from 7x to 15x, depending on the scene:

This is the kind of improvement one should expect from vectorizing your code. The decode job has disappeared from profiles and became barely noticeable.

Conclusion

Felix and I completed the translation of SSE to Neon code of a significant feature successfully. To be honest, I was happy that the functional part started working correctly relatively soon; having to spend days trying to debug SIMD code was a potential risk and a nightmare.

While profiling, we were able to greatly improve the runtime performance of the masked culling system; one of the jobs used in developer workflow became an order of magnitude faster. We also prepared a document with a list of potential further performance improvement of the feature.

Neon intrinsics in Burst that I had developed before proved to be working correctly. This is quite amazing to be able to write code in C# that is (almost) directly translated into assembly. Burst inspector is an amazing tool that helps you inspect the assembly of your C# jobs in realtime, as you write the code.

Optimization of DecodeMaskedDepthJob was a classical “think SIMD” task, almost as you see it in Andreas Fredriksson’s videos.

While profiling, we also identified a curious issue with Unity job system on Android that was investigated separately - I will write a separate post on this.

Looking back at this project, I think it was one of the most compelling and fun things I have done. Wish the world was full of such SIMD quizes…

The blog post may unfortunately miss some curious details because I am writing it much later from my memory.

The fate of Burst masked occlusion culling was unfortunately not favourable. It stayed with “experimental” label for some time until it was decided to abandon it and disband the team. A new occlusion culling feature was under development when I parted ways with Unity.

After Unity released C# CPU intrinsics with Burst, Microsoft developed a similar feature in .NET. I can’t for sure tell who was the first, but now .NET has support for CPU intrinsics, both Intel and Arm. The support for .NET intrinsics was planned for Burst, and may even have been released.